Insurance

12 articles

Homeowners insurance is a bundle of different categories of coverage, which apply in various situations. You aren’t able to pick and choose what categories you want – there are six different components to homeowners insurance, all of which are required, which we’ll discuss below. However, depending on your possessions, type of home, and your financial

According to 2021 data collected by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 97.3% of large firms — those with 50 full-time equivalent employees or more — offer health insurance to their employees. But just 31.9% of firms with fewer than 50 full-time employees offered health insurance benefits to employees. What accounts for the discrepancy? It’s largely because

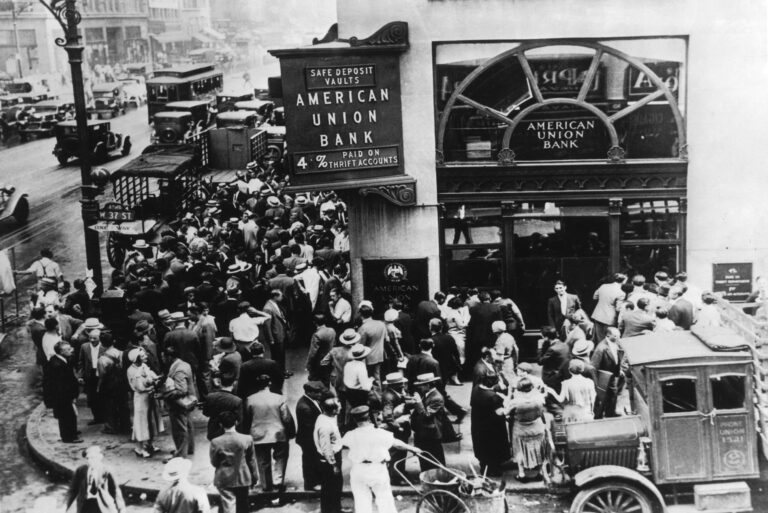

If you have a bank account – or even if not – you’ve likely heard of FDIC insurance. FDIC insurance is deposit insurance overseen by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, a federal entity created by the Banking Act of 1933. FDIC insurance guarantees the safety of deposits in checking, savings, and CD accounts held with FDIC

The FDIC hasn’t met its target reserve ratio in years. Should you be worried there won’t be any money if your bank fails? Probably not, but it’s more complicated than a simple yes or no.

Your bank’s “member FDIC” logo isn’t there for show. It means your money is insured in case something happens to the bank. Find out how much insurance you get, past, present, and future.

While it often gets overlooked, disability insurance is an important type of coverage that can protect you from the financial impact of an unexpected illness or injury. We’ve analyzed several disability insurance companies, comparing their benefits, cost, elimination period, and definition of disability. Read on to learn about the best disability insurance companies and determine

If you own certain types of businesses, your clients or customers may require you to provide a certificate of insurance. You may even need one for personal reasons. But how does a certificate of insurance differ from other types of proof of insurance, and how do you get one?

No two renters insurance companies are alike, so before choosing a policy, carefully consider each company’s relative strengths and weaknesses. These are our top picks for the best renters insurance companies to consider today.

Key person life insurance works a lot like a typical life insurance policy. But some of the biggest differences may affect whether it’s the right choice for you.

By limiting the costs of owning a sick or injured pet, pet health insurance spares many from the heartbreaking decision to prematurely put down a pet whose care is too expensive. These pet health insurance companies are the best, but they’re not interchangeable. Which one is right for you?

Next Insurance provides tailored business insurance policies and packages to small businesses in the United States. Learn about Next Insurance, its key features and what sets it apart, and whether it’s right for you.

Most people think of beneficiaries using life insurance after they die. But if you have a cash value life insurance policy, your insurance coverage is also quite useful while you’re still alive. But it’s crucial you understand how cash value works and all the fine print that comes with it.

Trending stories

Explore Protect Money

You don’t want to lose it. Learn how to keep it safe.